by Natalie Cordukes (Director, Paddington Children’s Centre)

As we entered the Cooee Gallery in Paddington, we were surrounded by a rich array of indigenous art and culture. At the back of the gallery, the whimsical fibre art sculptures made by the Tjanpi Desert Weavers caught the eye of the children; they evoked fascination and excitement amongst the group.

Our local gallery visit ignited an immediate interest in learning more about this cultural and traditional indigenous art practice. This provided the perfect extension for a group project the 4 years olds had been enjoying for months, including weaving, plaiting, threading and exploring the natural fibres of wool. Kolbe (2004, p.102) discusses that “remarkable things happen when children share and investigate a topic over days, weeks and even months”.

Joint exploration began, finding out as much as we could on the internet about the Tjanpi Desert Weavers. We were excited to learn that Tjanpi means grass, and this is what filled the animal sculptures. The group needed to return to the gallery for further investigation, so off we went in small groups to become further acquainted with the fascinating works from remote central Australia that were currently housed in ‘our Paddington’.

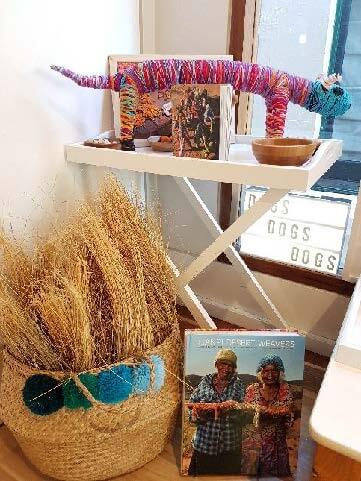

The children were particularly taken by a large colourful goanna made from grass, raffia and wool, named Tinka made by artist Molly Miller. Following many gallery visits, we decided that Tinka should come and join the Sun Room. We also purchased two story books by Ruth Rutherford that followed the journeys of other desert weaver animals in outback Australia. These books provided greater awareness and understanding about the contrasting landscapes, animals and language used in the desert lands of Australia.

Over the weeks that followed, Tinka became an integral part of the class, proudly placed in the middle of the morning group circle for our daily acknowledgment to country and discussions. The children decided at one of these meetings, that they would like to thank the Tjanpi Desert Weavers for Tinka. We also wanted to ask permission to make our very own class animal, in order to show respect for their creative technique. We were thrilled to receive a warm and encouraging response that sparked immediate weaving action. This two-way communication enriched the learning and engagement.

The children continued to explore the natural and synthetic fibres available in our art studio. They were practicing and connecting with the indigenous techniques using these raw materials to make yarn sticks and yarn teepees with sticks collected on local community walks.

The Cooee gallery were thrilled to hear about our project and that we had started a dialogue with the Tjanpi Desert Weavers. They provided us a DVD which captures the multisensory experience of the weavers, this deepened our curiosity and provided us further knowledge about how the sculptures are made.

The children started to discuss which animal best represents our local community, the group consensus was a dog! The children began to research dogs and represented their knowledge through drawings and discussion. Following this decision, we were very excited to find a new piece at the Cooee Gallery named Tiny Papa, papa meaning ‘dog’, he of course also joined the Sun Room family. As both Tjanpi animals joined the room, conversation sparked about what gender the animals were. Like many decisions made in the room, democratic process is used, through a voting system it was decided that Tinka is a girl and Tiny Papa is a boy. The Ruth Rutherford stories had provided an opportunity to explore culture and country that enticed interest in our own local cultural story.

Our correspondence and sharing continued with the very generous Tjanpi Desert Weavers. The warmth and connection between us was growing stronger despite the 2600km that separated us. We purchased picture books and other resources from their website and shared photos of our journey via email. We were thrilled to be included in their newsletter and to learn that some of the weavers were coming to Sydney for NAIDOC Week. Excitement erupted among the Educators, children and families to know that we would have an opportunity to weave with the very women we had been fascinated by for months.

In a weaving tent at Barangaroo at the Blak Markets, the educators, parents and children filled the tent in awe of the three very talented Tjanpi Desert Weavers that sat with us amongst a large colourful pile of raffia and tjanpi (grass). We felt privileged and emotional to be sharing in this wonderful opportunity, despite a language barrier, we felt a strong connection that guided our weaving skills and increased confidence.

We shared photos and stories from this experience and asked if we could have some grass to make our dog.

As promised the Tjanpi Desert Weavers sent down a large box of grass. When the box arrived the children danced, screamed and sang with joy to be receiving the tjanpi grass. They tore open the box and then carefully embraced, smelled and connected with the grass.

To say thank you we started to gather balls of wool that we collected from the families and sent them up to Alice Springs via our local post Paddington Post Office with the children. Our distant relationship was forging many new unexpected local connections.

Through our connections at the local gallery and the Blak Market, we contacted a local indigenous weaver, Aunty Karleen. She was engaged to work with the children to make their class dog. Through work with artists “children can learn how art makes connections around the world, across cultures and communities, and across time” (Wright, 2012, p.40). Together they began to work in small groups to manipulate the grass to form the structural base of the dog. They selected wool of varying vibrant colours that would guarantee a flamboyant and spectacular sculpture. Educators, Karleen and the children worked on the collective piece over many days, with our hands winding, twisting and knotting together over glorious stories shared by Karleen as we worked. This entangled art form led to deep connections with many indigenous people, each other and our local community and finally our dog was complete! Our learning was reaching far beyond the art of wool and creating a deep respect and understanding of indigenous culture. Yunkaporta (2012, p.8) echoes this sentiment that children should “learn through culture, not just about culture.”

Our dog needed a name and a plan of where we should visit in our local community. As the dog met our other two class animals, he stood at least 5 times the size of Tiny Papa, by consensus he was named Big Papa.

The children identified the key places in our local community where we would take Big Papa, and out the gates we went. He was introduced to local shops, dogs, neighbours and continued to establish relationships and opportunities to share in the celebration of our indigenous art journey, that had been going for well over 12 months. Big Papa was so popular in our local community that we started him a Facebook page which could allow families, Tjanpi Desert Weavers, Aunty Karleen and the Cooee Gallery to continue alongside us on our adventure.

From the beginning of this project, we were keen to make a story book, capturing our local area that could be shared with the Tjanpi Desert Weavers. Through our outings and adventures, we captured photos, quotes and children’s drawings to represent the experiences.

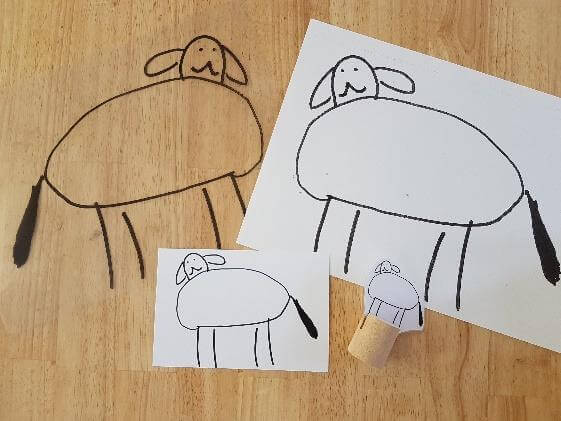

The children’s original dog drawings were reproduced by a photocopier to make small puppets (used for dramatic play and digital story building), large copies for

further wool art exploration and also transparencies that could be projected on large scales across our art studio walls, providing endless opportunities for creative exploration. Wright (2012, p.6) states that through the arts, children use a range of representational resources – visual, spatial, aural and physical – which merge and interact through multimodal thinking.”

Our relatable main character for our story book, Big Papa, helped us organise and brainstorm our thoughts. We revisited and discussed photos from excursions and especially enjoyed revisiting photos that included special guests such as Aunty Karleen and Uncle Jimmy. Uncle Jimmy is our local indigenous Elder, who spends time with the children and has enjoyed using Big Papa as a tool to connect and teach about our local lands and indigenous culture. This idea resonates with the Early Years Learning Framework which states “children develop their social and cultural heritage through engagement with Elders and community members” (DEEWR, 2009, p.23).

We collectively unleashed the imagination amongst the group, creating stories based on the children’s experiences and knowledge gained out in the community. Wright (2012, p.39) states that “art is not just about doing things. Through art children can learn about themselves, and feel a sense of belonging.”

This process has deepened our love and connection to the arts and our local context – Paddington. The project has supported a deep connection to place and country and an increased sense of belonging for all involved.

About the Tjanpi Desert Weavers

The Tjanpi Desert Weavers is a not-for-profit enterprise of Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Women’s Council (NPYWC). NPYWC members created Tjanpi (meaning grass) to enable women on the NPY lands to earn a regular income from selling their fibre art. More than 300+ Aboriginal women artists from 28 remote communities in the western and central deserts come together to create beautiful and intricate fibre art. “When we make Tjanpi work, sitting around with family and sharing stories. Sometimes joking around, sometimes talking serious, but always sharing stories…where we learn from each other.” (Jennifer Mitchell, Tjanpi Artist, Papulankuja WA) http://tjanpi.com.au/

Special mention to the 2017 Sun Room teachers and children, Tjanpi Desert Weavers, Aunty Karleen Green (Koori Artist) & Uncle Jimmy Smith (Koori Elder).